So I’m not entirely sure how much you all follow the news – at this point my hope is that you haven’t paid it much attention. The last thing I want is for you to be sitting with fear when all is fine with me.

If you have been frantically seeking out any bit of news on the recent conflicts in South Africa I’ll take a few minutes to catch you up on what is happening on this side of the world. Let me start by saying that I am fine, feel totally covered in prayer and work continues here at Kuyasa as usual.

The struggle that is happening here is common among around the world – the question of what do we do with foreigners that cross a border illegally, refugees seeking asylum. Zimbabwe has been in a very serious crisis for the past few years as a result of a dictator that has been doing what dictator’s do. The people are starving and dying, the rate of inflation is beyond imagination and I have heard it said that it is cheaper to use the money as toilet paper than to actually buy toilet paper. They have been living in conditions that I can’t begin to imagine and to be totally honest I really don’t want to most of the time. An election almost removed Mugabe (the current president) from office, but there was of course issues with tampering and it has taken the last few months to sort it all out. Meanwhile Mugabe uses the countries resources to begin beating and killing anyone that opposes him – so now one question becomes can the man who ran against Mugabe actually stay alive long enough to make it through the end of the election process. Only time will tell.

So of course the people of Zimbabwe have come flooding across the boarder into the neighboring and more affluent South Africa. They begin to start working illegally at jobs that pay them 30 Rand a day (about $4) and South Africans - particularly black South Africans – become angry that people are taking their jobs because they are willing to work for less money.

In JoBurg, some riots broke out that included attacks on foreigners (essentially any black that didn’t speak Xhosa or Zulu). Stores in townships were looted, people were beaten and killed and shacks were burned down. The media really hyped the incidents, enabling the hatred to spread quickly and providing criminals with reason to perpetrate crimes.

In my opinion, the root cause of all this hatred is actually tribal – it goes back centuries and children are taught from a very young age that to be proud of their tribe and in turn anyone that is different from you is less than.

At Kuyasa we were warned that if anything was going to break out in Kayamandi that it would likely happen over this past weekend, so extra security precautions were taken. They actually brought in 40 polices officers from Stellenbosch, which is good because in a lot of areas the police were aiding the criminals, but was bad because it meant that 40 white Afrikaners with guns were there for target practice. I was watching the news one night with Nana – and when a government official for the police force (a black man) was asked why it took them so long to take action in the townships, he actually used the words, “We are not trained to work with animals”.

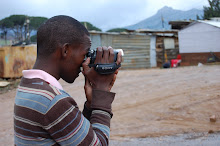

I had a film crew that was out finishing a project so I was waiting for them to return by the 6pm cut off. They didn’t make it back until 6:30pm and when I began to launch into the importance of them coming back on time, I could see on their faces that something was wrong. A few of my students began to tell me that things were falling apart beyond our protective gates. Riots had started near the police station and Somali owned shops were being broken into and looted. We were told that shots were being fired, but I never heard any gunfire and have not heard any confirmation about anyone being shot.

One of my students thought that it would be good to get some of the action on video – when another Kayamandi resident put a gun to his side and told him to stop filming. My student explained that you couldn’t see anything because of the dark and the man with the gun said that if he tried to film again that he would be shot.

I was nervous, but really not scared. I knew that the attacks were not aimed at me – so my only concern was now driving out of Kayamandi amongst a greedy mob. As we watched the mob take every item from a shop just outside the gate, my good friend Mbongeni said that today he was embarrassed to be an African.

In reality, it was nothing compared with the Los Angeles riots – but a few of my students went home and cried. They were very saddened watching people in their community treat others with such disregard.

Within two hours all looting and chaos was finished. And we have not seen any other flare-ups in Kayamandi since. Please continue to pray for Zimbabwe and South Africa that these Xenophobic attacks would cease and be replaced with love for one another.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

Love in any Language

My good friend and 16-year-old roommate Nana is teaching me a lot about the differences between American and Xhosa culture. There are a lot of differences of course and she has had to adjust to many things as a Xhosa living with a couple of Molungus (white people).

One of the things that stands out to Nana is the ease with which we say the words “I love you”. She explains that the words “I love you” are only used in a boyfriend/girlfriend relationship – and that they of course rarely mean anything. Of course when it comes to the molungus in the flat, we are constantly telling Nana how much we love her. She thinks it’s funny and giggles once in awhile but I know that she loves it. Who doesn’t love to be told that they are loved, even if it does feel out of the ordinary?

The first time she heard the words she made a mental note that maybe these white people didn’t actually mean it – but in her words, “You each just keep on saying it – and I began to figure that if you didn’t really mean it – you would forget to say it. So you must really mean it.”

Nana likes to joke about the fact that one time her best friend told her that she loved her – and Nana’s response to her friend was, “Are you dying or something?”

One night while we were chatting about how odd she finds it – and about how it’s not “part of her culture”. She turns to me and mentions that when she has children, she’s going to tell them how much she loves them.

While I thought it a small victory for this molungu, it speaks to one of the biggest lessons that I feel I’m learning while I’m here. Culture is important. But it’s up to us as individuals to find what works and is beautiful about our culture and strive to keep it. And it’s equally as important to move away from what doesn’t work, and learn how other societies have managed to succeed.

One of the things that stands out to Nana is the ease with which we say the words “I love you”. She explains that the words “I love you” are only used in a boyfriend/girlfriend relationship – and that they of course rarely mean anything. Of course when it comes to the molungus in the flat, we are constantly telling Nana how much we love her. She thinks it’s funny and giggles once in awhile but I know that she loves it. Who doesn’t love to be told that they are loved, even if it does feel out of the ordinary?

The first time she heard the words she made a mental note that maybe these white people didn’t actually mean it – but in her words, “You each just keep on saying it – and I began to figure that if you didn’t really mean it – you would forget to say it. So you must really mean it.”

Nana likes to joke about the fact that one time her best friend told her that she loved her – and Nana’s response to her friend was, “Are you dying or something?”

One night while we were chatting about how odd she finds it – and about how it’s not “part of her culture”. She turns to me and mentions that when she has children, she’s going to tell them how much she loves them.

While I thought it a small victory for this molungu, it speaks to one of the biggest lessons that I feel I’m learning while I’m here. Culture is important. But it’s up to us as individuals to find what works and is beautiful about our culture and strive to keep it. And it’s equally as important to move away from what doesn’t work, and learn how other societies have managed to succeed.

Thursday, May 15, 2008

Some Things Just Grow On You...And Some Things Never Will

I've come to the conclusion that there are a lot of things to which you can become accustomed - and there are just some things that you will never get used to seeing.

I have been living with Mama Shumi for a month, and I have grown such a deep love and respect for her that it kind of surprised me the other day. My good friend Jenna has moved up North to live near her fiance's farm. Which means that my other good friend Cindy is looking for a roommate and help caring for a 16-year-old named Nana that I have come to love very much. So tomorrow I will be moving out of Mama Shumi's place and into the flat with Cindy and Nana. I'm happy to be moving, and I cherish the time it will give me with Nana - but when I thought about leaving Mama Shumi it made me very sad. I honestly didn't know that I had grown to love this chicken feet lady so much! She has taught me many things - and from her I have learned to enjoy SA soap operas, eat dinner in the presence of tubs of chicken feet and live in peace with small roaches in the kitchen. I love her dearly.

The other day I had my first bite of a chicken foot - and I think I can say with confidence that I doubt I'll ever have another. The flavor was fine, it's the texture of the tough scaly skin that's unpleasant. Don't get me wrong, I only had a small bite - I was far from biting off a toe like my sisi Nana did with ease. I'm not sure that chicken feet is ever a meal that I will be able to embrace.

Another thing that always gets me here is the age at which children become responsible for other children. We have young babies at our feeding scheme - one-year-olds that are being cared for by their four-year-old sisters. I watched closely the other day while a young girl consoled her baby brother by pulling him close to her and rocking him back and forth. This child is not old enough to take care of herself let alone take care of another. When I thought about what it would look like if my sister told my niece (age 3) to walk down the road for lunch and watch over her brother (18 months) it made me cringe. It's something with which I don't think I'll ever become accustom.

I have been living with Mama Shumi for a month, and I have grown such a deep love and respect for her that it kind of surprised me the other day. My good friend Jenna has moved up North to live near her fiance's farm. Which means that my other good friend Cindy is looking for a roommate and help caring for a 16-year-old named Nana that I have come to love very much. So tomorrow I will be moving out of Mama Shumi's place and into the flat with Cindy and Nana. I'm happy to be moving, and I cherish the time it will give me with Nana - but when I thought about leaving Mama Shumi it made me very sad. I honestly didn't know that I had grown to love this chicken feet lady so much! She has taught me many things - and from her I have learned to enjoy SA soap operas, eat dinner in the presence of tubs of chicken feet and live in peace with small roaches in the kitchen. I love her dearly.

The other day I had my first bite of a chicken foot - and I think I can say with confidence that I doubt I'll ever have another. The flavor was fine, it's the texture of the tough scaly skin that's unpleasant. Don't get me wrong, I only had a small bite - I was far from biting off a toe like my sisi Nana did with ease. I'm not sure that chicken feet is ever a meal that I will be able to embrace.

Another thing that always gets me here is the age at which children become responsible for other children. We have young babies at our feeding scheme - one-year-olds that are being cared for by their four-year-old sisters. I watched closely the other day while a young girl consoled her baby brother by pulling him close to her and rocking him back and forth. This child is not old enough to take care of herself let alone take care of another. When I thought about what it would look like if my sister told my niece (age 3) to walk down the road for lunch and watch over her brother (18 months) it made me cringe. It's something with which I don't think I'll ever become accustom.

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

A Unique Breakthrough

This last week I invited my students to come to the center on Saturday and watch an Academy Award winning documentary “Born Into Brothels”. It’s an incredible documentary and if you haven’t seen it, I can’t recommend it highly enough. The doc is about 8 young children living in the red light district in India - and their lives are built around the profession of their mothers – prostitution. All of the young girls face the reality that once they are old enough they will also be forced into working “the line”.

An American woman that has been living in India for some time taking pictures, and she gives a camera to each child and begins to the children how to take pictures. The journey for each child is amazing.

There were several small breakthroughs as a result of this documentary. First, almost the entire class showed up to view it. I know this sounds like a silly thing to be grateful for, but it was not a requirement to show up. Also, understand that what I have been prepared for was a very high drop out rate. Some programs start here with 30 students and end with 3. It’s only been two weeks, but I’ve yet to lose one student.

Second, after watching the documentary several students asked me when this was made. At first I didn’t understand why they were asking this question, and I told them that it wasn’t that long ago, I think it won the award in 2001 or somewhere close. The reason they asked that question blew me away, they couldn’t believe that there were people living in these conditions right now. So here we have a group of students, a few of which are living in small brick homes, and most of whom are living in shacks. From the American point of view, Kayamandi represents the poorest of the poor – and you will never find an informal settlement like this in the states. But still their hearts were broken over the conditions in which these children were living.

One of my female students came to me fighting back tears. Her question stopped me in my tracks, “How do we change the world so that no one lives like this anymore?” The first thought that popped into my mind that I did not express is that no one needs to live like this – that there is enough wealth in this world that no one needs to go hungry. Don’t get me wrong - I’m not a communist - far from it in fact. I don’t feel guilty for living in America, I feel blessed! Americans work really hard for what they have – and give a great deal of it away again to benefit others. But the fact remains that many live in abject poverty, while others live with more than they could ever need.

So my response to her was that sometimes people don’t look outsides themselves – they worry about their own lives and their own families and give little thought to others until something moves them to do so. Then I reminded her that there were people in her community that were living in a poverty that is similar to what they saw in this documentary. She agreed and started to think through a potential life change for herself, “Maybe I don’t need children. Maybe the best way to help is to care for other young children that need love.” Wait for it, it gets better when you know the life situation of this young girl, abandoned by her parents and living with an aunt that she believes doesn’t love her. She has spoken to me before about a poem that she once read about a mother’s love, and after examining all the characteristics that the author equated to the love of a mother, she came to the conclusion that her mother was not any of those things for her and therefore her mother didn’t love her. What an amazing revelation, in a culture that believes there is something wrong with you if you’re married and can’t have children, to come to the conclusion that being a safe haven for unwanted or orphaned children might be your contribution to ending poverty in your community.

The final breakthrough was a small personal victory for me. In Kayamandi, it is estimated that about 1 in 3 people are infected with HIV. It’s always a big topic of discussion and few people get tested because of the stigma that surrounds the disease. So while many are infected, few resolve to actually deal with it. In the documentary, the teacher tries to get each of these students into a boarding school. There are several things that need to fall into place for this to happen, and one requirement is that they have HIV tests, and if any child is infected then they won’t be accepted to the school. When the results are revealed and we learn that all of the children are negative – my entire class started clapping with joy – and one even uttered the words “maybe we should all go to get tested as a class…”

An American woman that has been living in India for some time taking pictures, and she gives a camera to each child and begins to the children how to take pictures. The journey for each child is amazing.

There were several small breakthroughs as a result of this documentary. First, almost the entire class showed up to view it. I know this sounds like a silly thing to be grateful for, but it was not a requirement to show up. Also, understand that what I have been prepared for was a very high drop out rate. Some programs start here with 30 students and end with 3. It’s only been two weeks, but I’ve yet to lose one student.

Second, after watching the documentary several students asked me when this was made. At first I didn’t understand why they were asking this question, and I told them that it wasn’t that long ago, I think it won the award in 2001 or somewhere close. The reason they asked that question blew me away, they couldn’t believe that there were people living in these conditions right now. So here we have a group of students, a few of which are living in small brick homes, and most of whom are living in shacks. From the American point of view, Kayamandi represents the poorest of the poor – and you will never find an informal settlement like this in the states. But still their hearts were broken over the conditions in which these children were living.

One of my female students came to me fighting back tears. Her question stopped me in my tracks, “How do we change the world so that no one lives like this anymore?” The first thought that popped into my mind that I did not express is that no one needs to live like this – that there is enough wealth in this world that no one needs to go hungry. Don’t get me wrong - I’m not a communist - far from it in fact. I don’t feel guilty for living in America, I feel blessed! Americans work really hard for what they have – and give a great deal of it away again to benefit others. But the fact remains that many live in abject poverty, while others live with more than they could ever need.

So my response to her was that sometimes people don’t look outsides themselves – they worry about their own lives and their own families and give little thought to others until something moves them to do so. Then I reminded her that there were people in her community that were living in a poverty that is similar to what they saw in this documentary. She agreed and started to think through a potential life change for herself, “Maybe I don’t need children. Maybe the best way to help is to care for other young children that need love.” Wait for it, it gets better when you know the life situation of this young girl, abandoned by her parents and living with an aunt that she believes doesn’t love her. She has spoken to me before about a poem that she once read about a mother’s love, and after examining all the characteristics that the author equated to the love of a mother, she came to the conclusion that her mother was not any of those things for her and therefore her mother didn’t love her. What an amazing revelation, in a culture that believes there is something wrong with you if you’re married and can’t have children, to come to the conclusion that being a safe haven for unwanted or orphaned children might be your contribution to ending poverty in your community.

The final breakthrough was a small personal victory for me. In Kayamandi, it is estimated that about 1 in 3 people are infected with HIV. It’s always a big topic of discussion and few people get tested because of the stigma that surrounds the disease. So while many are infected, few resolve to actually deal with it. In the documentary, the teacher tries to get each of these students into a boarding school. There are several things that need to fall into place for this to happen, and one requirement is that they have HIV tests, and if any child is infected then they won’t be accepted to the school. When the results are revealed and we learn that all of the children are negative – my entire class started clapping with joy – and one even uttered the words “maybe we should all go to get tested as a class…”

Wednesday, May 7, 2008

Evidently I'm famous

So in South Africa they have this tradition – there is a specific man called an Imbongi that is given the job of essentially shouting before the President. It works something like this, if Nelson Mandela is walking through a crowd, this man jumps around and crouches down shouting in poetic form about the wonder that is the president. I was commenting to the kids how funny this was to me, mostly because I don’t understand the language, so it looks like a crazy man jumping around and screaming in a crowd of people.

I also have an Imbongi – and her name is Nana. She is one of my film students and she wants to work in “media”. The word media is used a lot here – and it pretty much is the word that I hear from every student. When I ask them to tell me what aspect of media specifically they don’t really know. Nana is a very talented writer, so we have been discussing a journalism future, but she also wants to be famous so we’re thinking maybe a news anchor. ☺

Nana pretty much thinks that anyone that works “in media” is famous. Even to the point of posing for pictures with the man that is hired to take photos of the 10k, calling him paparazzi . So when Nana first learned what I do I had to explain it several times so that she would understand that I’m not famous, I just once in awhile run into people that are famous. When I enter a room where Nana has gone before me, I am often flooded with students that joke about wanting my autograph and tell me that they had no idea I was a producer on Spider-man. Funny, I didn’t know I was a producer on Spider-man either. I should make a few calls about residual checks…

I also have an Imbongi – and her name is Nana. She is one of my film students and she wants to work in “media”. The word media is used a lot here – and it pretty much is the word that I hear from every student. When I ask them to tell me what aspect of media specifically they don’t really know. Nana is a very talented writer, so we have been discussing a journalism future, but she also wants to be famous so we’re thinking maybe a news anchor. ☺

Nana pretty much thinks that anyone that works “in media” is famous. Even to the point of posing for pictures with the man that is hired to take photos of the 10k, calling him paparazzi . So when Nana first learned what I do I had to explain it several times so that she would understand that I’m not famous, I just once in awhile run into people that are famous. When I enter a room where Nana has gone before me, I am often flooded with students that joke about wanting my autograph and tell me that they had no idea I was a producer on Spider-man. Funny, I didn’t know I was a producer on Spider-man either. I should make a few calls about residual checks…

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)